Space Mining and International Law: Risks, Rules, and Future Investments

Introduction

Space mining — the extraction of minerals, metals, and water ice from celestial bodies like the Moon and asteroids — is transitioning from science fiction to strategic business planning.

With rare-earth shortages on Earth, companies and governments are looking to space as the next frontier for sustainable resources.

However, as the technology advances, a critical question arises: who actually owns what in space?

This article explores the legal framework, international debates, and investment implications shaping the future of space resource utilization.

Why Space Mining Matters for Investors

The economic rationale for space mining is strengthening for three main reasons:

- In-space demand is real: Water ice can be converted into fuel for lunar or Martian missions.

- Technology costs are falling: Autonomous robotics, reusable rockets, and in-situ processing are cutting mission expenses.

- Policy signals are emerging: More nations now support commercial resource extraction rights, even while prohibiting sovereignty over celestial bodies.

Together, these factors make the 2030s a likely decade for the first economically viable mining operations beyond Earth.

The Legal Framework: Treaties That Define Space Ownership

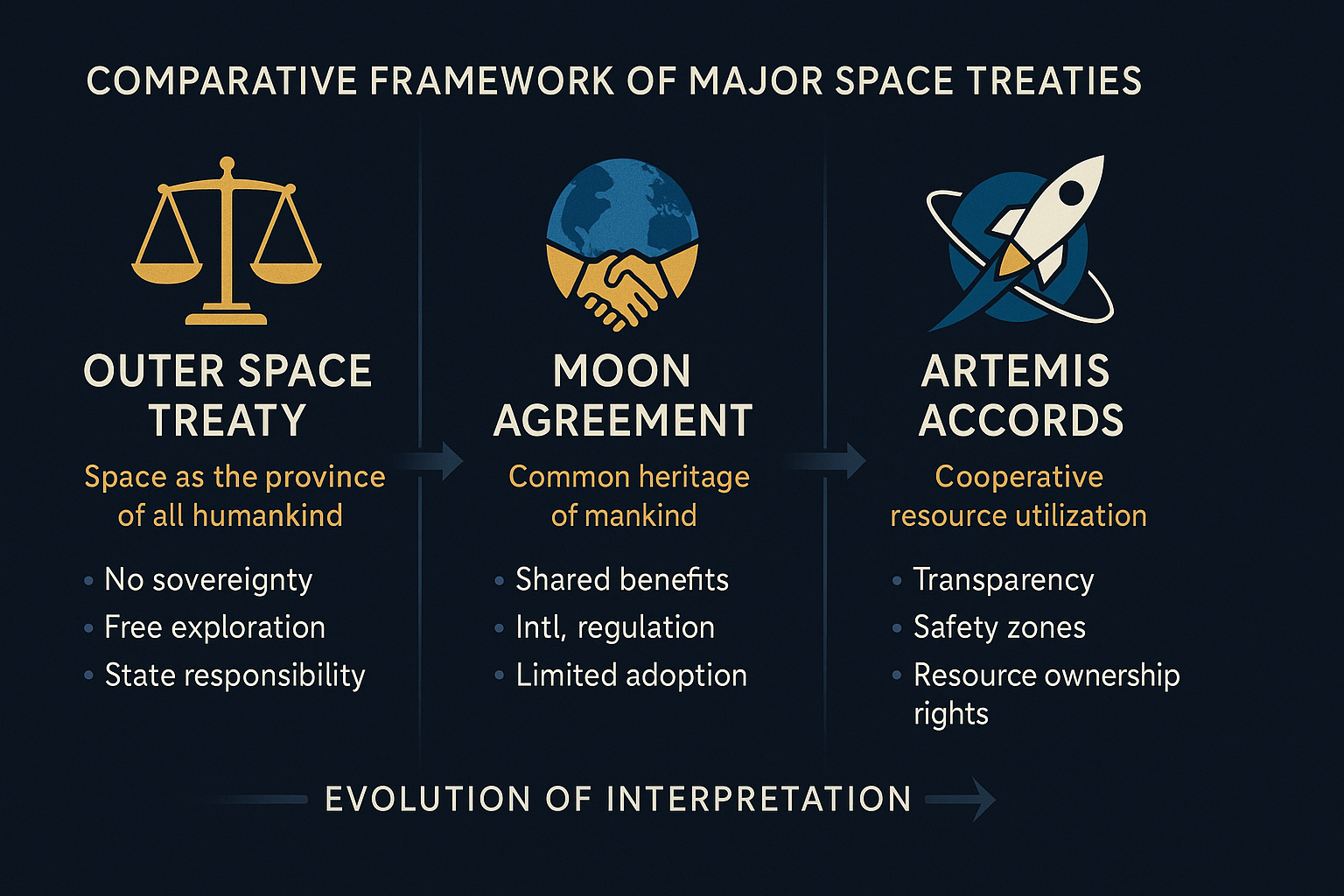

The Outer Space Treaty (1967)

The Outer Space Treaty (OST) is the cornerstone of international space law.

It establishes that space is the “province of all humankind,” and no nation can claim sovereignty over celestial bodies.

However, it also allows for the “use and exploration” of space by all states.

For private companies, this means they must operate under the authorization and supervision of their home country — which is legally responsible for their actions in space.

The Moon Agreement (1979)

The Moon Agreement attempted to regulate lunar and asteroid resource extraction by designating them as the “common heritage of mankind.”

However, major spacefaring nations (including the U.S., Russia, and China) never ratified it, limiting its legal impact today.

The Artemis Accords (2020s)

The Artemis Accords, initiated by the United States and joined by dozens of countries, reinterpret the OST in modern terms.

They permit the extraction and ownership of resources, provided operations are transparent and avoid harmful interference with others.

Key principles include:

- Transparency and interoperability

- Safety zones instead of territorial claims

- Preservation of heritage sites

This “norms-based” approach is becoming the de facto legal standard for international space cooperation.

Can Companies Own What They Mine?

While no one can own the Moon or an asteroid, many national laws now affirm that materials extracted from space can be owned, used, and sold.

- U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (2015): Grants American citizens rights to resources they extract.

- Luxembourg Space Resources Act (2017): Allows companies to claim ownership of extracted materials with government authorization.

- Japan and UAE: Have introduced similar laws encouraging private space ventures.

This emerging legal consensus means mining rights are shifting from territorial to transactional — what you extract is yours, but where you mine is still everyone’s.

Key Legal and Ethical Challenges

1. Liability and Environmental Risk

Under the OST, states are liable for damages caused by their private entities.

This raises insurance, licensing, and cross-border liability concerns for investors and insurers alike.

2. Planetary Protection

Mining operations could contaminate pristine environments.

The Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) and national agencies are drafting planetary protection standards to limit biological and chemical contamination.

3. Conflict Prevention

As multiple actors target similar asteroid clusters, the definition of “safety zones” may blur into de facto territorial claims — something international law will need to clarify to avoid disputes.

4. Data and Export Control

Space mining technologies often involve AI, sensors, and propulsion systems restricted by export laws.

Multinational partnerships must navigate complex technology transfer regulations.

The Investment Landscape

Space mining will likely progress in three commercial phases:

- Exploration: Small robotic missions identifying high-value targets.

- Extraction and Processing: Deploying modular mining systems to extract and refine water or metals.

- Distribution: Building infrastructure for in-space trade — fuel depots, transport hubs, and material markets.

Investors are eyeing early-stage companies developing in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) technologies, robotic excavators, and chemical processing systems for space environments.

Conclusion — Law, Profit, and the Next Frontier

Space mining sits at the intersection of law, economics, and human ambition.

The emerging legal order doesn’t grant sovereignty but allows ownership of extracted materials, creating a workable foundation for investment.

The next decade will determine whether these frameworks can balance innovation with fairness — ensuring that the riches of the solar system benefit humanity as a whole, not just the first movers.

Sources

- United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) — Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space (1967)

- NASA Artemis Accords (2024 Update)

- U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (2015)

- European Space Policy Institute (ESPI Report, 2025)