Data Sovereignty & Cloud Localization: Laws, Security, and Legal Risks in 2025

Data sovereignty has evolved from a policy buzzword into a strategic requirement for global organizations. As governments tighten control over how data is collected, stored, and transferred, enterprises operating across multiple jurisdictions must balance compliance, security, and scalability. The challenge: national laws are fragmenting the digital world, forcing cloud providers and customers to rethink architecture, governance, and cross-border operations.

1. What Data Sovereignty Really Means

Data sovereignty means that data is subject to the laws of the country where it is stored or processed.

Data residency refers to a business decision to locate data in a specific region for performance, privacy, or cost reasons.

Data localization is a legal mandate that certain types of data — for example, healthcare records, financial transactions, or government information — must remain within national borders.

While these terms are often used interchangeably, their implications differ sharply. Sovereignty concerns jurisdiction and authority, residency is strategic choice, and localization is legal obligation.

2. Why Governments Push Data Localization

- National security and surveillance concerns: Reducing foreign access or intelligence risks.

- Privacy and consumer protection: Ensuring that local citizens’ data is governed by domestic laws.

- Economic development: Encouraging investment in domestic data centers and local cloud ecosystems.

- Regulatory leverage: Strengthening national control over critical infrastructure, finance, and communications sectors.

In essence, localization is a tool for digital sovereignty — and a means of asserting political and economic independence in the digital age.

3. Global Landscape — How the Rules Differ

European Union (EU):

The GDPR remains the cornerstone of European data protection. Cross-border transfers are only allowed through adequacy decisions, Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), or Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs). The EU–U.S. Data Privacy Framework has restored partial transfer routes, but organizations must still conduct risk assessments and maintain encryption safeguards.

United States:

The U.S. does not have a national data localization law. Instead, a patchwork of sectoral regulations — such as HIPAA for healthcare and GLBA for finance — governs data protection. However, the CLOUD Act grants U.S. authorities potential access to data held by American providers abroad, raising sovereignty concerns for other nations.

China:

The Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and Data Security Law (DSL) impose stringent controls. “Critical” and “important” data must remain onshore, and cross-border transfers require government security assessments.

India:

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP, 2023) allows cross-border transfers to “trusted” countries but still enforces localization in key sectors such as telecom and payments. Sector regulators like the Reserve Bank of India and TRAI retain authority to demand in-country processing.

Japan and South Korea:

Both countries rely on strong privacy laws and international adequacy decisions. For critical sectors like finance and public administration, additional residency or certification requirements apply.

Middle East and GCC:

Nations such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE are leading in “sovereign cloud” models. Public sector workloads must reside within national borders, often using locally operated cloud regions managed by global providers under government oversight.

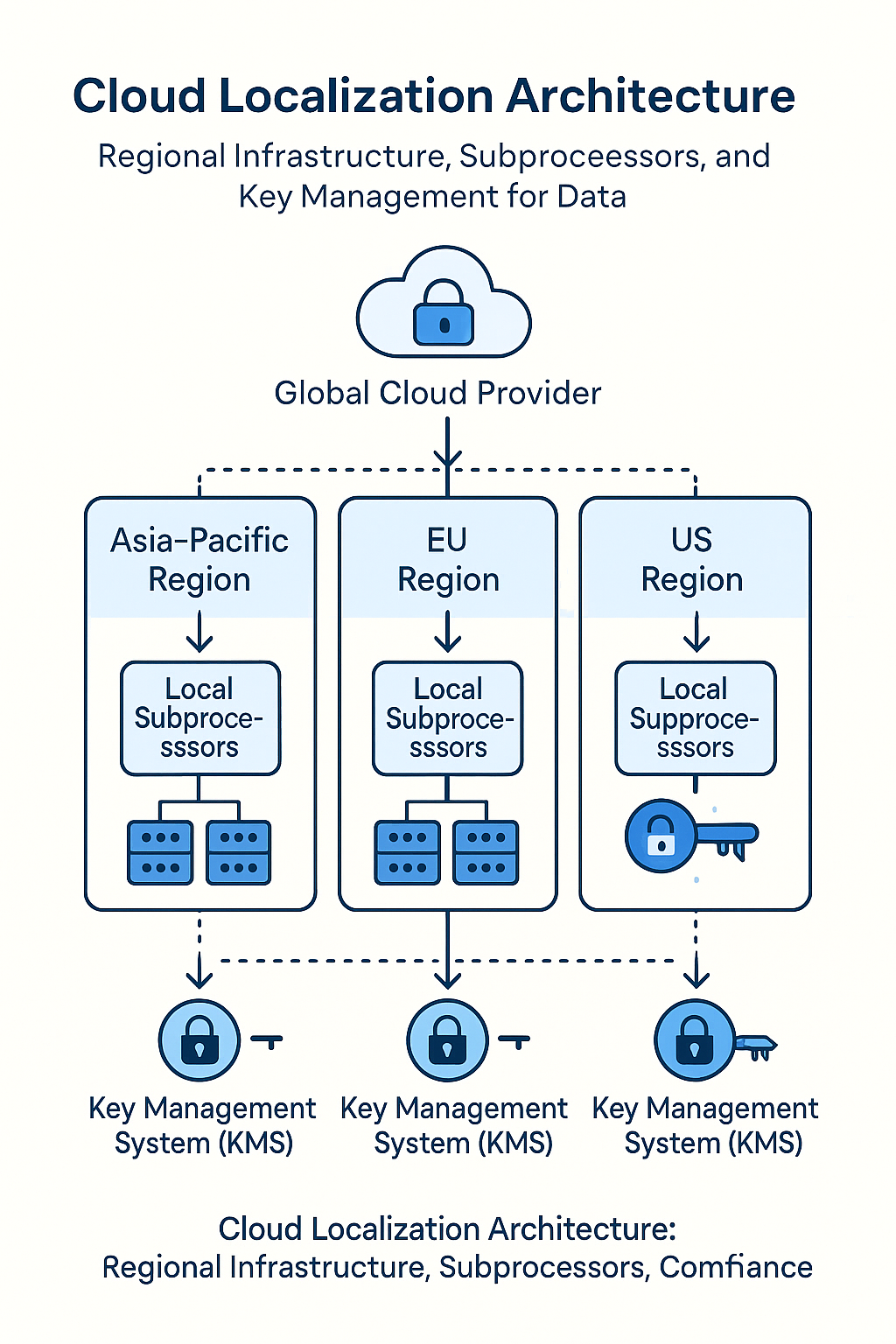

4. Cloud Security Strategies for Localization Compliance

1) Regional segregation and egress control:

Keep sensitive data within local regions. Use “deny by default” network egress rules and explicit allowlists for any outbound data transfer.

2) Sovereign or dedicated cloud models:

Leverage region-specific instances or sovereign variants offered by hyperscalers (e.g., AWS Dedicated Region, Azure Sovereign Cloud, Google Distributed Cloud Hosted) to meet local regulatory needs.

3) Encryption and key sovereignty:

Use customer-managed encryption keys (CMEK) or hold keys within domestic hardware security modules (HSMs). This ensures that even the provider cannot access unencrypted data.

4) Data classification and routing:

Label data by jurisdiction and sensitivity, then automate storage and transfer rules via policy engines. Ensure that backups and logs also comply with localization rules.

5) Legal and compliance governance:

Maintain country-by-country compliance matrices. Engage local counsel to interpret overlapping frameworks (GDPR, PIPL, DPDP, LGPD, etc.). Audit cloud vendors for subprocessor and regional data flow transparency.

5. Legal Risks and Conflicts of Law

The biggest legal tension arises when one country’s compliance requirement contradicts another’s. For instance:

- The U.S. CLOUD Act may compel disclosure of data stored in the EU, conflicting with GDPR restrictions.

- China’s cybersecurity and export review laws can block outbound data flows required for multinational analytics.

- European courts (e.g., Schrems II ruling) have invalidated previous transatlantic data frameworks due to government access concerns.

Multinational companies must, therefore, build conflict-of-law mitigation plans — such as encryption-at-rest with local key ownership, data minimization, pseudonymization, and independent audit trails.

6. Emerging Solutions and Architecture Models

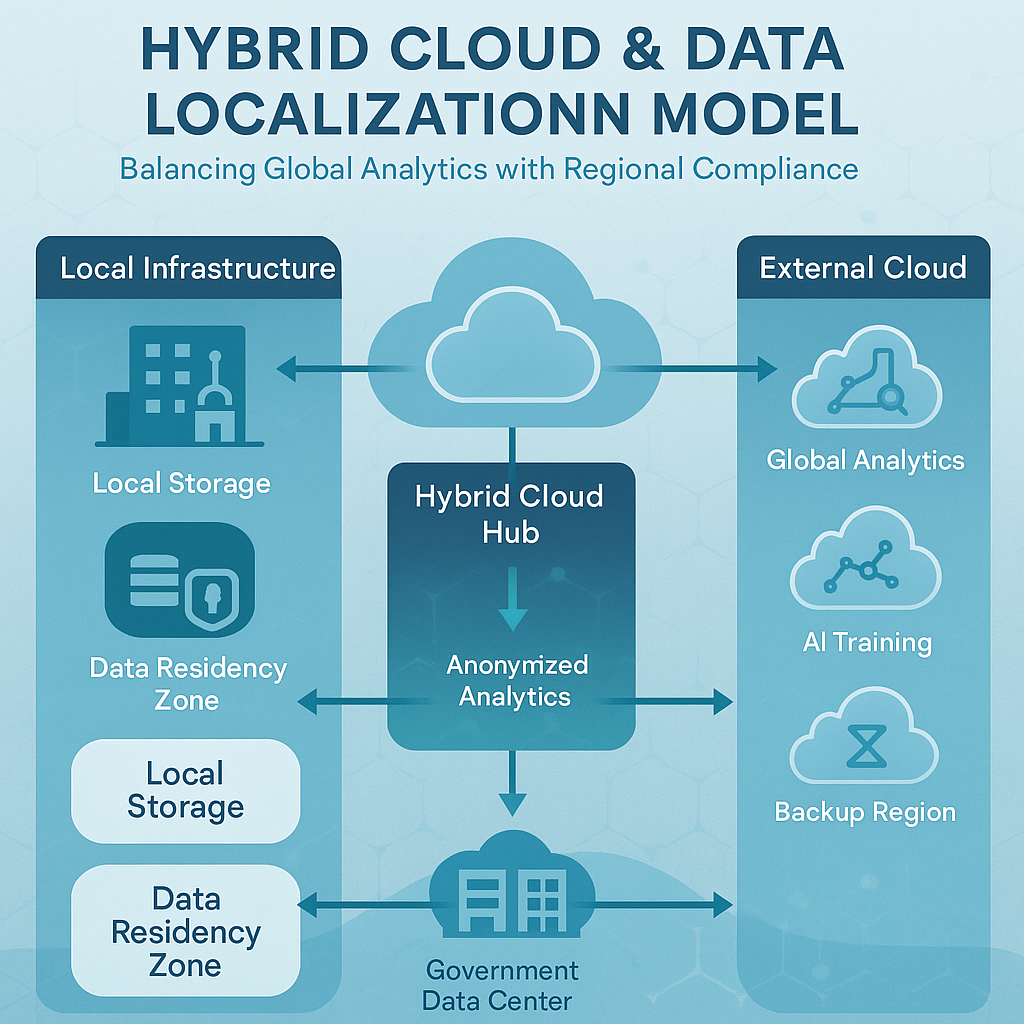

- Hybrid-cloud and multi-cloud: Allowing workloads to remain local while integrating global analytics through anonymized or federated models.

- Data trust frameworks: Governments are experimenting with trusted digital infrastructure partnerships (e.g., EU Gaia-X, Japan’s Trusted Web).

- Privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs): Secure enclaves, homomorphic encryption, and differential privacy are being used to process sensitive data without physical transfer.

- AI sovereignty integration: Localization rules increasingly extend to AI training data, forcing companies to keep datasets regionally segmented.

7. What Enterprises Should Do Now

- Inventory and classify data — map all data assets by country of origin and storage region.

- Review contracts and subprocessors — ensure third parties comply with local data regulations.

- Adopt encryption and key localization — prioritize “hold your own key” (HYOK) models.

- Update governance policies — include country-specific storage and transfer requirements.

- Engage legal, compliance, and IT teams together — data sovereignty is not just a technical issue; it’s a legal one.

Conclusion — A Fragmented but Inevitable Future

Data sovereignty will continue reshaping the global cloud market throughout the 2020s. The trend is clear: more regional control, more regulation, and less data fluidity. Yet, with well-designed architectures — hybrid deployment, localized keys, and privacy-by-design principles — businesses can remain compliant without losing global efficiency.

The organizations that succeed in this new landscape will treat sovereignty as a core pillar of their digital strategy, not a compliance afterthought.

Sources

- European Commission — GDPR & Data Transfer Guidance (2025)

- U.S. Department of Commerce — Data Privacy Framework (2024)

- Chinese CAC — Data Security Law (2023)

- India DPDP Act (2023)

- ENISA — Cloud Security & Sovereignty Report (2024)

- Gartner — “Data Localization Trends and Global Cloud Compliance” (2025)